Do climate-related exclusions have an effect on portfolio risk and diversification? A contribution to the ‘Article 9’ funds controversy

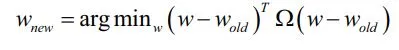

- Out of 161 funds reporting a ‘sustainable investment objective’ in accordance with the European sustainable financial disclosure regulation (article 9), 50 contain stocks of companies involved in coal, oil and gas or aviation. These stocks represent on average 2.8% of the funds’ invested capital.

- Excluding these stocks with a naive (pro rata) reallocation leads to an average tracking error of 0.53% with the original portfolio. Sector deviations occur mainly in the ‘Energy’ and ‘Utility’ sectors. In terms of fundamentals, exclusions increase exposure to higher ‘quality’ stocks, whereas exposure to ‘investment’ and ‘value’ stocks is slightly reduced.

- Excluding these stocks with an optimised reallocation technique further reduces the average tracking error to 0.42%, while also reducing fundamental differences between the original and optimised portfolio. These results suggest that excluding climate controversial stocks has overall a limited impact on the risk profiles of the funds.

Introduction

With the increase in funds claiming to be ‘responsible’, ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’, the regulators are clarifying the scope of these funds to prevent ‘financial greenwashing’. As part of its Action Plan for Sustainable Finance, the European Union (EU) now imposes, through its Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), reporting requirements that depend on the ambition of the funds: funds that claim to have a ‘sustainable investment objective’ must comply with ‘Article 9’ requirements, while funds that highlight environmental or social characteristics as part of a broader investment strategy must comply with ‘Article 8’ requirements. These two categories of reporting requirements have promptly been considered by the market as ‘labels’ associated with the funds, Article 9 funds being the most ambitious in terms of extra-financial impact. However, the reporting requirements of the SFDR leave room for interpretation of the definition of a ‘sustainable’ investment, as well as flexibility with respect to the levers to be used to achieve the ‘sustainable investment objective’: exclusions, reallocation, shareholder engagement.

The flexibility left to managers in the implementation of impact strategies is at the root of a significant controversy concerning funds considered as ‘Article 9’. In November 2022, two investigative journalism platforms – Follow the money and Investico – published the Great Green Investment Investigation (GGII) in collaboration with a dozen European media.1 They revealed that nearly half of the 838 European ‘Article 9’ funds had invested in companies that are involved in the fossil fuels and aviation sectors and that the journalists identified as significant contributors to global warming due to their lack of ‘a credible climate strategy’. Following this investigation and other controversies, 40% of the initial ‘Article 9’ funds – many of these being passive funds tracking EU Climate Transition and Paris-Aligned benchmarks – were voluntarily downgraded to ‘Article 8’ by the fund managers at the end of 2022, according to Morningstar.2 Several reasons may explain the holding of these controversial stocks in sustainable portfolios: data discrepancies in the assessment of their environmental impact, a willingness to engage with the company as a shareholder with the objective of improving their practice, or a strategy of gradual exclusion.

Whatever the reason, a question that arises sooner or later for the asset manager is to know what would be the impact of excluding these controversial stocks on the performance and risk profile of the fund.

There is no consensus on the existing literature whether the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in investment funds affects the financial performance of the funds (Friede, Busch and Bassen [2015]). One of the reasons for this lack of consensus is the broad spectrum of practices that fall under ‘integration’ of ESG criteria. Among these different practices, several studies have investigated the effect of the exclusion of stocks, with mixed results (eg, Khajenouri and Schmidt [2021]; Capelle-Blancard and Monjon [2014]). Even when focusing on the exclusion of fossil fuels, the effect on funds’ performance remains uncertain: Henriques and Sadorsky (2018) find negative effects while Trinks et al (2018) find no difference and Hunt and Weber (2019) find positive effects. Our study aims to contribute to this literature by focusing on the effects of exclusion on risks rather than short-term performance: what would be the impact of excluding stocks associated with climate change on the risk profile of funds that have a ‘sustainable investment objective’ (‘Article 9’) funds? The risk profile of a fund is responsible for its long-term performance patterns and should therefore be a primary concern for managers.

Data and model

As there is no consensus on the definition of sustainable funds, we present in this section the criteria used to build our sample of funds, as well as the ESG data used to identify controversial stocks related to climate change. We finally present the risk metrics used to study the effects of exclusions on fiduciary liability.

Sample of sustainable funds

To avoid defining a new subjective criterion for considering a fund to be sustainable, our sample is composed of funds that meet the more stringent criteria of the SFDR, ie, funds that have a ‘sustainable investment objective’ and must therefore comply with ‘Article 9’ requirements.3 These sample criteria are in line with those used by the GGII but differ in the observation date: our sample list has been extracted as of July 2023 while the sample list of the GGII has been extracted as of the 30 June 2022. Following – among other things – the controversies that arose in the wake of the GGII, around 40% of Article 9 funds were reclassified as Article 8 by the end of 2022. We can therefore expect the results obtained from our sample to differ from those obtained by the GGII as a result of this wave of reclassification.

We excluded funds with historical tracks of less than a year, as well as funds with more than 1% of their holdings in emerging countries. Also, we only considered funds whose composition is available and accounts for at least 85% of the capital invested. Our sample thus contains 161 ‘Article 9’ funds that contain a total of 2,362 stocks.

Criteria for climate-related exclusion

To identify the controversial companies that should therefore be excluded, we rely as far as possible on the same criteria and data as the GGII. We used Bloomberg’s sector classification ‘airlines’ and ‘airport development/maintenance’ to identify companies involved in the aviation sector, and Urgewald’s4 Global Coal Exit List (GCEL) and Global Oil & Gas Exit List (GOGEL) to identify companies involved in the coal, oil and gas sectors. The GCEL is a list of 2,799 companies involved in coal production5, based on a database that covers the entire thermal coal value chain. Similarly, the GOGEL is a list of 901 companies – responsible for 95% of the world’s oil and gas production – operating in upstream and/or midstream subsectors.6

Risk profile of the funds

To assess the impact of exclusions on the funds’ risk profile, we analyse several key indicators. First, we estimate the tracking error between the screened and the initial funds7 using a sample covariance matrix normalised with the methodology proposed in Ledoit and Wolf (2003). We also measure the impact of exclusions on sectors weights8, as well as exposures to traditional risk factors. For the latter, we use the five-factors model of Fama and French (2015), and obtain factor exposures (or betas) by estimating the following regression on the last five years of daily returns

where Rit represents the return of the ith fund, the returns of the local market factor are denoted by RMt and eit is the error term. There are different sets of risk factors for every geographical region, and hence exposures are evaluated with the set corresponding to the region where the company is domiciled, which can be any of North America, Europe, Japan or Asia Pacific ex-Japan. Exposures to the SMB (small minus big) and HML (high minus low) factors are associated with small stocks and good-value stocks, respectively. Stocks exposed to the RMW (robust minus weak) factor are associated with high-quality companies, whereas those exposed to the CMA (conservative minus aggressive) factor with companies that invest conservatively.

Exclusion methods

We apply two methods to perform exclusions from the funds’ portfolio. The first, that we call naive, is an exclusion followed by a pro-rata reweighting of the portfolio remaining stocks.9 This method assumes that an investment manager sells the controversial positions and reinvests the proceedings in the remaining equity positions proportionally to their initial weight.

The second method is based on a tracking error minimisation between the original portfolio and the new portfolio that does not contain the excluded stocks. The new portfolio is therefore the solution to the minimisation program:

Here the covariance matrix is the same sample covariance matrix normalised with the methodology proposed in Ledoit and Wolf (2003) that we use to measure the ex-post tracking error.10 Here portfolios are long-only and their budget constraint is set so that the old and new portfolio have the same amount of capital invested. The resulting portfolios correspond to the action of an investment manager who would sell the controversial positions and reinvest the proceeds in a way that reduces the impact of the exclusions on the risk of the portfolio. It will therefore favour re-investments in stocks with risk profiles as close as possible to the excluded ones.

Results

Despite the wave of reclassification from Article 9 to Article 8 funds, almost a third of our fund sample still contains controversial climate-related stocks. We show that excluding these stocks would have small effects on the risk profiles of the funds and that these effects can be reduced by optimising the reallocation.

Investments in controversial climate-related stocks

In our sample of 161 funds, 50 funds contain stocks whose underlying companies are involved in at least one of the three climate-related controversial activities – coal, other fossil fuels and aviation (representing 60 different stocks). While being one of the most controversial activities, involvement in coal is the most frequently encountered criterion, both in terms of number of stocks and number of funds (figure 1).

From a regional perspective, the companies involved in the controversial activities are mainly located in Europe and North America (figure 2), which is in line with the region distribution of the funds in our sample (nearly half are based in Europe and over a third in the US). In proportion, controversial stocks represent 2.3% of the number of stocks in our sample based in Europe (in line with North America), while this figure is approximately twice as large for Asia-Pacific.

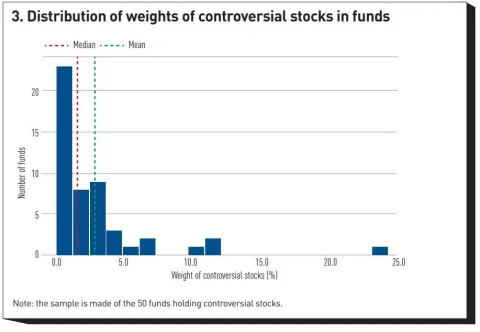

When it comes to weights into funds, the share of controversial stocks in our sample of sustainable funds is on average 2.82%. However, this number is driven by three funds with extreme values: 50% of the funds have less than 1.60% of their weight invested in controversial stocks (figure 3). The three funds with the highest share of controversial stocks are infrastructure investment funds that have committed to investing in infrastructure companies aligned with sustainability objectives for at least a given share of their assets. This suggests that the remaining share of the assets are not subject to sustainable criteria.

Effects of exclusion on tracking error

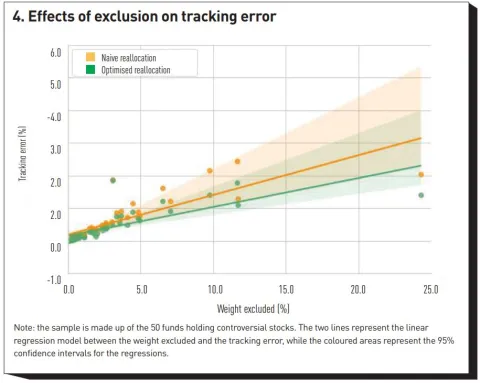

Excluding stocks with a naive reallocation leads to a relative tracking error (between the fund after exclusion and the fund before exclusion) of 0.53% on average (the median is 0.32%), which is low. The reallocation technique based on tracking error minimisation slightly reduces this number, with an average ex-post relative tracking error of 0.40% (the median is 0.23%). The tracking error is on average proportional to the total weight of excluded stocks (figure 4). For some funds, excluding controversial stocks would induce a tracking error above 1.00%. In these cases, the optimised reallocation method is particularly efficient, as it produces much lower tracking errors than the naive method.

Effects of exclusion on sector allocation

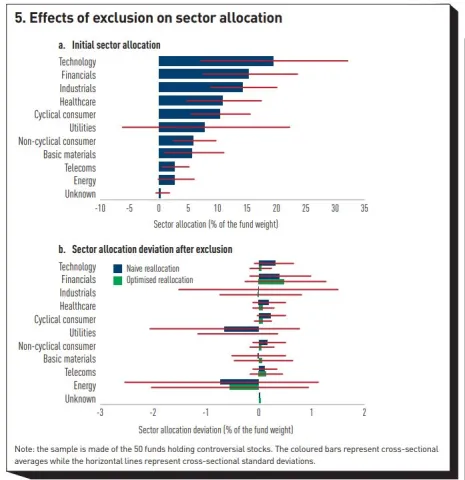

The exclusion mainly leads to sector allocation deviations in the Energy and Utilities sectors (absolute deviations of respectively -0.72% and -0.65%, figure 5b), which is consistent with excluding companies in the fossil fuel industry. The result for the Industrials sector is less intuitive, as the average deviation is close to 0% while the sector is the one highly represented in excluded stocks (23/60, through aviation). This is mainly due to a compensation effect: aviation, which represents a small share of the Industrials sector is excluded but the remaining allocation to the Industrials sector increases during the reallocation process as the sector represents an important share of the initial allocation (figure 5a).

Compared to the initial allocation, the most important relative deviation concerns the Energy sector with the sector weight falling on average from 2.66% to 1.94% (which represents a relative deviation of 27%). The optimisation does not reduce overall sector deviations: the reduction of deviation for the Energy and Utilities sectors is compensated by an increase in deviation for Financials, Telecoms and Basic materials sectors.

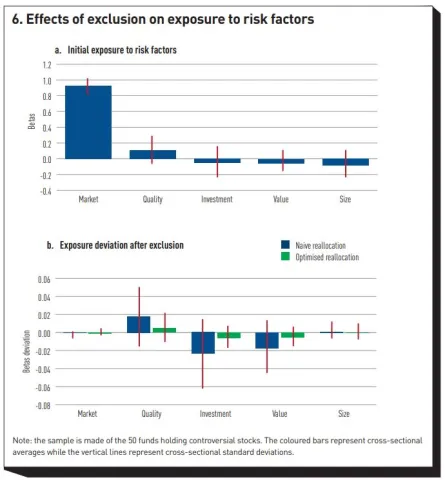

Effects of exclusion on exposure to risk factors

The exclusion with naive reallocation increases funds average exposure to the Quality (RMW) factor (from 0.11 to 0.13) and decreases average exposure to the Investment (CMA) and Value (HML) factors (from -0.05 to -0.07, figure 6). These results can be explained by the factor exposure of the controversial stocks and their sectors. The 18 companies involved in ‘oil and gas activities’ and the 21 companies involved in ‘aviation’ have for example a significant negative exposure to the Quality factor. Excluding these companies therefore leads to an increased exposure of funds to this factor. Similarly, the companies involved in the three controversial activities have a strong positive exposure to the Investment and Value factors, therefore leading to a decreased exposure of funds to these factors after exclusion.

From a risk management perspective, these deviations are not trivial. However, the optimisation method significantly limits the exposure deviation to these factors (figure 6b).

Conclusion

This article contributes to the literature on the effects of excluding controversial stocks on the funds’ financial performance (Henriques and Sadorsky [2018]; Trinks et al. 2018 and Hunt and Weber [2019]). In order to be closer to the asset managers’ concerns and constraints, we propose to shift our focus from performance to risk profile. We seek to understand whether fiduciary liability might explain why asset managers have chosen to hold these controversial stocks in their sustainable portfolios.

Following the 2022 investigation published by a consortium of a dozen European media, we analyse for 161 funds that have a ‘sustainable investment objective’ according to the European sustainable financial disclosure regulation (Article 9) the effects of excluding stocks involved in coal, fossil fuels and aviation on the funds’ tracking error, sector allocation and exposure to the Fama and French (2015) five factors.

As of 2023, we show that of over 161 funds that have a ‘sustainable investment objective’ according to the European sustainable financial disclosure regulation (Article 9), 50 still contain stocks of companies involved in coal, oil and gas or aviation despite the 2022 wave of reclassification from Article 9 to Article 8.

The exclusion of these stocks even with a naive reallocation has a limited effect on the tracking error and sector diversification of the funds. The results are consistent with those from Trinks et al (2018)’s long-term analysis, ie, the average impact on the tracking error of excluding climate-related stocks11 is small but increases with the weight of excluded stocks. In some cases, we show that exclusion causes nontrivial deviations in exposure to the Quality, Investment and Value risk factors. However, we show that a risk minimisation method can significantly reduce these deviations.

Finally, our results suggest that holding these stocks in sustainable funds is not justified from a risk perspective. In order to guarantee the credibility of these funds, it therefore seems essential that asset managers justify the holding of these stocks, either by differences on the assessment of their belonging to controversial sectors (data discrepancy), or by a shareholder engagement policy aimed at improving the practices of the underlying companies.

However, these results should not be generalised to all exclusion practices and to all funds: they concern specific climate-related criteria as well as funds claiming a sustainable objective. One avenue of research could be to extend the analysis of the effects of exclusion on risk metrics to other exclusion criteria, including social and governance issues on a broader universe of funds. In these cases, it will be particularly interesting to disentangle the impact on the tracking error due to the weight of excluded stocks - which is likely to be higher - from deviations in exposure to factors linked to exclusion, and from changes in the proportion of unexplained risk.

References

- Capelle-Blancard, G., and S. Monjon (2014). The performance of socially responsible funds: Does the screening process matter? European Financial Management 20(3): 494-520.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 116(1): 1-22.

- Friede, G., T. Busch and A. Bassen (2015). ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 5(4): 210-233.

- Henriques, I., and P. Sadorsky (2018). Investor implications of divesting from fossil fuels. Global Finance Journal 38: 30-44.

- Hunt, C., and O. Weber (2019). Fossil fuel divestment strategies: Financial and carbon-related consequences. Organization & Environment 32(1): 41-61.

- Khajenouri, D. C., and J.H. Schmidt (2021). Standard or Sustainable-Which Offers Better Performance for the Passive Investor? Journal of Applied Finance & Banking 11(1): 61-71 (forthcoming).

- Ledoit, O., and M. Wolf (2003). Improved estimation of the covariance matrix of stock returns with an application to portfolio selection. Journal of Empirical Finance 10(5): 603-621.

- Trinks, A., B. Scholtens, M. Mulder and L. Dam (2018). Fossil fuel divestment and portfolio performance. Ecological Economics 146: 740-748.